Reverse Engineering Dark Souls 3 Networking (#4 - Reliable UDP)

Recap

In the previous posts we’ve seen how the game connects to an initial introduction server, which then forwards game onto a second key-exchange/authentication server, before finally forwarding the game onto a third and final server.

This last server is going to be the most interesting, as it’s the main “game server” which handles everything needed to support the online game features in Dark Souls 3. We’re going to look at how this third server now. This is going to be a dense post, so prepare yourself!

Protocol Confusion

So lets dive in and see what we’re looking at here. Your first assumption may be to try treating this server like the others, and assuming it uses the same TCP-based protocol. However if we start listening to that TCP port the game was forwarded to by the last server, you will be disappointed to see that the game never attempts to connect on this port.

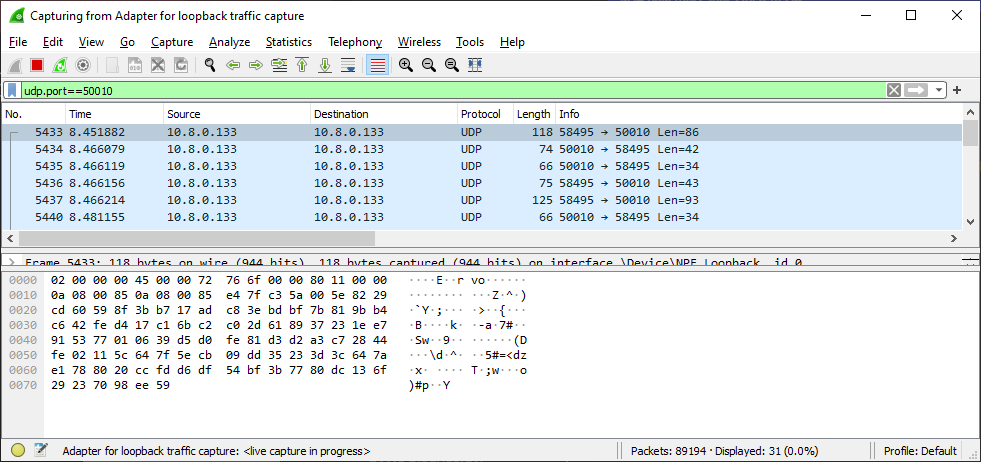

So what exactly is going on here? If we break out Wireshark again we can see what, and more importantly where, the client is sending its packets.

It appears the client has switched over from TCP to UDP for communicating with the game server. And even more problematic, if we try parsing the packets in the same way as those we received via TCP we will fail.

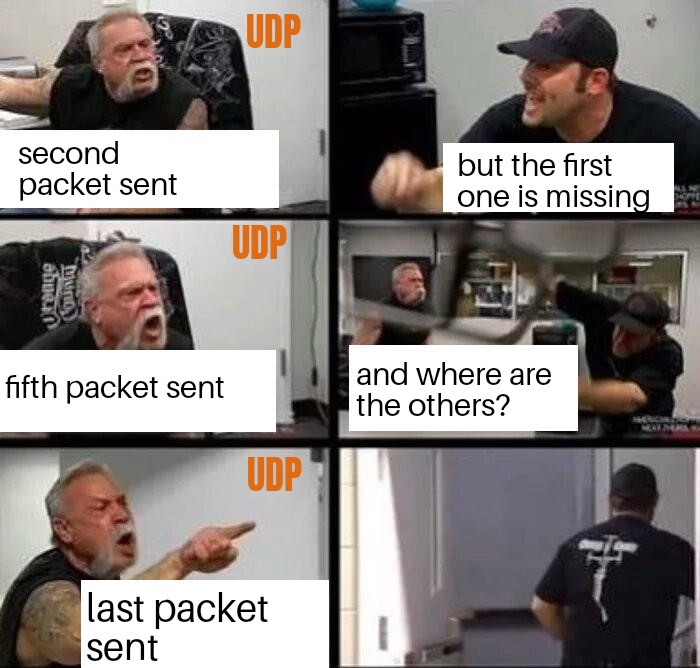

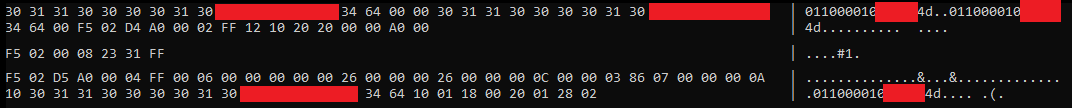

If we have a look at the first packets data we can see why:

The protocol has entirely changed!

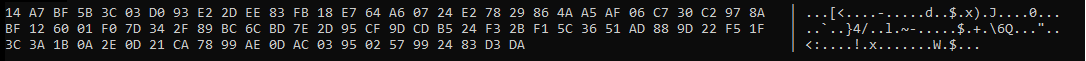

Well back to square one, if take a capture of several packets we can start to breakdown the contents once again.

We can see that the first 8 bytes are always identical, followed by what we can assume is a ciphered payload.

So what is the first 8 bytes? Well it changes every time we go through the connection process, but remains the same for each connection. And if we examine the data sent by the authentication server in the previous post, we can find the same 8 bytes in the first field of Frpg2GameServerInfo struct.

What these bytes work as is essentially a token created by the previous server to say that we have authenticated ourselves correctly, and are allowed to access the game server.

If the server receives packets without an authentication token it recognizes, it will ignore the packet.

Now how about that ciphered data after the authentication token? Fortunately we have one giant hint about how to decrypt this - Remember the second key exchange we performed on the previous server? Well it turns out that was to generate the key that is used for all communications with this server. If we try to decrypt this packet using the same CWC cipher we used on the previous server, we will suddenly get something a bit more meaningful!

Parts redacted to obscure my steam id.

Parts redacted to obscure my steam id.

Excellent! We have something we can work with here.

A Logical Jump

So I’m going to have to apologies a little bit here, and make a logical jump. Deciphering how these packets work is unfortunately a long, and fairly dull, exercise in reading through disassembly, which will fill up several blogs posts. So instead I’m going to explain directly how they work.

I leave it as an exercise for the reader if they wish to investigate further. A good starting point is reading through the code associated with the Nauru::Communication::UDPConnection class.

Reliable UDP

So the protocol for these packets is one that anyone who has done networking code in game development will be familiar with. It’s an implementation of reliable UDP.

A little background information here for those unfamiliar with network protocols - if you know what reliable UDP is, feel free to skip this section.

The two most commonly used protocols are known as TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) and UDP (User Datagram Protocol). Each have their positives and negatives.

TCP is stream-orientated protocol. By that we mean that at the application layer each side of the connection just seems a continual stream of bytes sent from the other side, there is no segmentation into “packets”. In additional to that, TCP is also reliable and ordered. Meaning that each byte of data sent will be reliably delivered to the other end of the connection, and will be received in the same order it is sent.

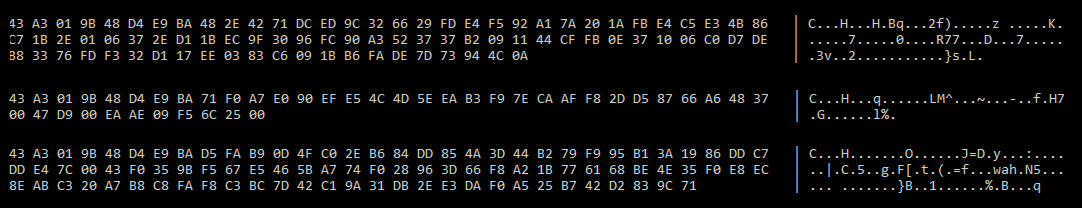

UDP is the polar opposite of TCP. UDP is stateless, meaning that no connection or stream exists concept on the application layer. Instead the application will just receive any packets (known as datagrams in UDP terminology) that are received by the host for the UDP port the application is listening on. All sends and receives occur as individual packets, these packets have a maximum size dictated by the minimum MTU (Maximum Transmission Unit) setting on the network devices between the sender and the receiver, typically around 1024 bytes, data sent beyond this size may be fragmented during transmission. Importantly UDP is unordered and unreliable - Meaning packets are not guaranteed to get to their destination, and if they do, they are not guaranteed to come in the same order they were sent.

Source unknown, this meme has been going around for years.

You might ask why would a game server choose to use UDP rather than TCP? It seems that TCP would be the preferred choice right? Well that’s not always the case, especially in video games. TCP excels for things like sending a web-page to a web-browser, something where reliability and ordering is important. However with this functionality comes a lot of additional overhead to manage the stream, along with complex algorithms for flow and congestion control, which may result in high latency or sluggish transmissions.

Video games on the other hand, generally don’t need the guarantees that TCP provides. For example if a game server is sending the positions of other players/enemies/etc to a client every frame, with TCP if one of those updates was lost, the recipient’s game would not receive any data until retransmission occurs, which can take several hundred millisecond - dozens of frames. By the time the recipient actually receives that retransmission the data isn’t relevant anymore.

Using UDP in this situation allows us ignore the dropped update packet and just carry on when we get the next update. We might get some questionable position extrapolation, or rubber banding, but at least we can continue without waiting dozens of frames.

In additional, UDP has one very useful feature that TCP doesn’t. With UDP we can reliably implement NAT traversal by using a technique called Hole Punching. This allows us to make direct connections to different devices on different networks. Allowing users to host games without worrying about things like port-forwarding.

However you might guess that there are some things that games normally want to send with the reliability and ordering of TCP. The naïve approach to supporting this might be to use both TCP and UDP in tandem. But this adds a lot of complexity and we loose some of the benefits of using UDP.

Instead what we can do is implement a reliability layer on top of UDP, that behaves similarly to how TCP does, that we can selectively use for the packets we want to be reliable and ordered. This is precisely what Dark Souls 3 does.

Exactly why the game uses this protocol though, I’m a little unsure of. Nothing the game server does is latency sensitive, everything has to be both ordered and reliable, and none of the other benefits like nat traversal are helpful to it. TCP would have suited just fine for the usage. I’m guessing the reason is either something related to scalability (maximum tcp connections a server can handle?) or perhaps the protocol is just reuse of some existing code? Either way, this is what the game uses, so what we will have to replicate.

Packet Structure

So back to those packets! How exactly are they structured? Well like the TCP protocols they have a short header followed by an optional data payload.

There is one small quirk here. The first packet that’s sent by the client is always prefixed with a small struct containing two copies of the players steam id.

struct initial_packet_prefix

{

char steam_id[17];

char null = 0;

char steam_id_copy[17];

};

struct packet_header

{

uint16_t magic = 0x02F5;

uint8_t sequence[3];

uint32_t type;

uint8_t congestion = 0xFF;

};

- The magic field remains the same for all packets.

- The congestion field changes depending on network state, and can be used to adjust the frequency of data sent - ds3os ignores it for simplicity.

- The sequence field contains 2x 12-bit values (3 nibbles each). We call the first one the local ack and the second one the remote ack. There usage depends on the type of packet.

- The type of packet can be any of the following values. There are other types that the game can process, but none of them are used in practice, so we only handle this subset. You can view the full set in the DS3OS codebase.

enum class packet_types

{

SYN = 0x02,

DAT = 0x04,

HBT = 0x05,

FIN = 0x06,

RST = 0x07,

// These are combination types, they are the type above

// bitwise OR'd with 0x30.

ACK = 0x31,

SYN_ACK = 0x32,

DAT_ACK = 0x34,

FIN_ACK = 0x36,

};

Establishing Connections

Each side of the connection maintains a sequence-number, this sequence number is sent in the sequence field of the header. When a packet is recieved an acknowledgement (ACK) packet is sent back to the sender containing the sequence number contained in the recieved packets header. If one side of the connection doesn’t receive an acknowledgement of a packet it sent, then after a certain amount of time it will attempt to resend it. After a certain amount of re-sends fail the connection is considered broken.

Each side of the connection also keeps track of the next sequence number it expects to receive from the other side, if it receives a packet with an older sequence number than expected it assumes its ACK of that sequence number got lost and re-sends it, if it gets a sequence number greater than what it expects then it assumes its missed a packet and waits for the older packet to be resent.

This allows us to maintain both a reliable stream of packets, as well as keeping them ordered.

However before any of this will work we need to synchronize sequence numbers so that both sides of the connection know what the other sides sequence number is.

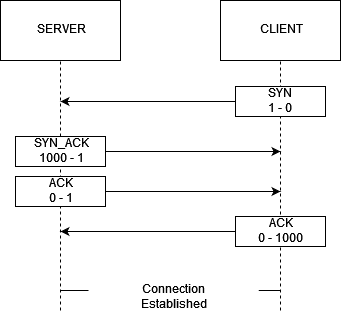

This is done by a sequence of packets known as a handshake. If you’ve ever read about the TCP three way handshake, then this will look very familiar.

Sequence numbers traditionally start out as randomized, though its not strictly necessary, in this example the clients sequence numbers start at 1 and the servers at 1000.

- The client first sends a

SYN(Synchronize) packet to the server with their sequence number in it. - The server then sends back an

SYN_ACK(Synchronize Acknowledge) packet with their sequence number in it and the sequence number the client sent. - The client then sends back an

ACK(Acknowledge) packet with theSYN_ACK’s sequence number in it.

At this point both sides of the connection know what the others sequence number is and have acknowledge that they know it. At this point the connection can start exchanging data, each side will expect the next packet from the other side to always have a sequence number of sequence+1.

If communications fails at any point, due to issues such as dropped packets, a RST (Reset) packet will sent, triggering re-randomizing sequence numbers, and then the handshake will be re-started from the beginning.

Termination of connections behaves in almost the same way as establishing them, with a three-way-handshake. The only difference is FIN and FIN_ACK are used rather than SYN and SYN_ACK.

Data Exchange

Ok now we have a connection established!

So how do we actually exchange data? Well its yet another three way process.

- First one end of the connection sends a

DAT(data) type packet, with a payload containing the data we want to send. - The receiving end then sends a

DAT_ACK(Data Acknowledge) packet back, with it’s remote sequence number set to the sequence number of the initialDATpacket. If this is a reply with additional data (eg. data requested by theDATpacket), then the payload contains that additional data. - The initial side sends a

ACK(Acknowledge) packet with the remote sequence number of theDAT_ACKpacket.

It’s very important that DAT_ACK packets are sent, even if no reply is required. Not doing so will cause the game to timeout and consider the connection broken.

As the game tends to send data as infrequently as it can, if there is a long period with no data exchanged each side will send a HBT (Heartbeat) type packet to let the other side know they are still there. If no data or heartbeat is seen for a while the connection is considered broken.

Packet Payloads

Ok, so we’re now able to send and receive data packets, all done, we can start looking at the what the game packets do right?

Unfortunately not …

Like the TCP protocol used in the previous servers the data we want is actually wrapped in two different protocol layers. So we need to know how to parse these before we get to the game-data we are actually interested in.

Fortunately these ones are quite straightforward, much simpler than the the reliable udp protocol!

Fragmentation

As I mentioned earlier, the maximum amount of data you can send in a UDP packet is limited to the MTU of all the network devices along the route between the sender and receiver. Typically the safest amount of data you can send in a UDP packet is about 1024 bytes.

What happens if we want to send more than that? If we just send a packet larger than that, it will be fragmented by one or more of the network devices along the route between the sender and receiver. And given any of those fragments may be any size, come in any order, and may even be lost, we have no way to reassemble these fragments when we receive them, even with our reliable udp implementation.

So what Dark Souls 3 does instead is to pre-fragment the data and sending it in multiple packets, such that no individual packet length is over the safe limit of 1024 bytes.

To allow us to reassemble the data a small header is included at the start of each fragment received.

struct fragment_header

{

uint16_t packet_counter;

uint8_t compress_flag;

uint8_t unknown_1;

uint8_t unknown_2;

uint8_t unknown_3;

uint16_t total_payload_length;

uint8_t unknown_4;

uint8_t fragment_index;

uint16_t fragment_length;

};

The packet_counter field increments for every un-fragmented block of data thats sent.

The fragment_index field increments for each fragment of data that makes up the full payload, the first fragment being 0, the next being 1, etc.

The fragment_length field contains how many bytes of data are included in this fragment.

The fragment_payload_length field contains how many bytes of data are included in the complete un-fragmented data.

To receive the data we just keep reading fragments (which will already be in order thanks to our reliable-udp implementation) and appending their data together until the sum is greater than total_payload_length.

To further squeeze as much data as they can into individual packets, if the compress_flag field is set then the completed un-fragmented data was encoded using DEFLATE Compression before being fragmented up and sent.

Game Messages

The last layer you might remember from the TCP protocol, its almost exactly the same. It’s a small wrapper that tells us what type of message is contained in the remaining data, which like the TCP protocol is encoded as protobuf!

To do so each block of data contains the following small header:

struct message_header

{

uint32_t header_size = 0x0C;

uint32_t message_type;

uint32_t message_index;

};

- The header_size field is constant, and presumably is there for potential variable length headers, though they aren’t used by the game.

- The message_index field is a constantly incrementing sequence number, which is used to identify individual messages and the replies to them.

- The message_type field contains a unique identifier that matches one of the protobufs we can deserialize.

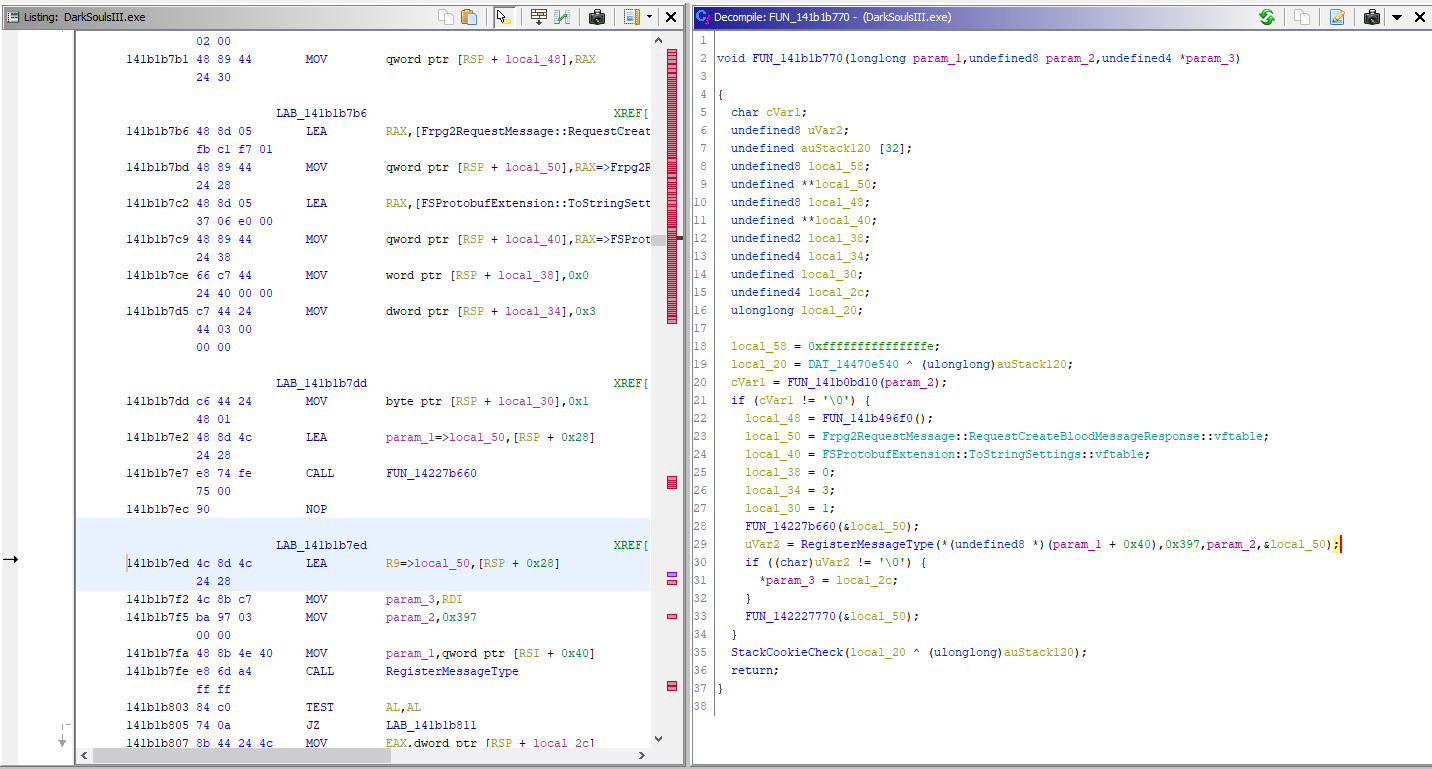

The game messages are quite easy to handle, we just read the message_type and deserialize the data with the appropriate protobuf. But how do we know what protobuf matches each value? Well surprisingly this is actually super easy.

If we break out Ghidra and try simply searching for the names of different protobufs (which we know already from the RTTI information), we will find a function like this for each of them. It is essentially registering the protobuf as a valid message, and the function that that is invoked, which I’ve called “RegisterMessageType”, contains the id of the message as its second parameter (in this case RequestCreateBloodMessageResponse has an id of 0x0397).

Dark Souls 3’s game server protocol is setup in a Request->Response architecture, the game asks for something and then the server responds to it. You can see this in the names of all the protobufs, which almost all come in pairs, eg. RequestCreateSign and RequestCreateSignResponse.

To know which message a response is for, every response message has a message_type of 0 and a message_index set to the same message_index of the original request message. A little book-keeping is necessary so we know what Response protobuf we need to decode based on the Request protobuf we originally sent.

The game server protocol also has a small handful of push messages that the server can send without a request from the client. These all have a message_type value of 0x0320. To identify the protobuf for these push messages, the type of the protobuf is stored in the first field of the protobuf - meaning you need to deserialize twice, once with a protobuf containing a single id field, and once with the actual full protobuf. For example this is the protobuf for one of the push messages:

message PushRequestNotifyRingBell {

required PushMessageId push_message_id = 1;

required uint32 player_id = 2;

required uint32 online_area_id = 3;

required bytes data = 4;

}

To get the Id of the protobuf to use we would first deserialize it with this cutdown protobuf:

message PushRequestHeader {

required PushMessageId push_message_id = 1;

}

Why exactly they choose to do it this way I have no idea, its obtuse and unnecessary seeing as they already had a message_type field. I’m guessing it might have just ended up cobbled together like that over time.

Coming Up

Phew, that was a long post. But at least we now know how the game communicates with the server. And we can decipher all the messages it sends. We’re now in a position to start looking at high level logic that contains the game features, which is what’s coming up in the next post!