Reverse Engineering Dark Souls 3 Networking (#2 - Packets)

Recap

In the previous part of this series I went over how we can make the game connect to our own server.

This part starts to look into the structure of the protocol the client uses to communicate with the server.

The Packet Structure

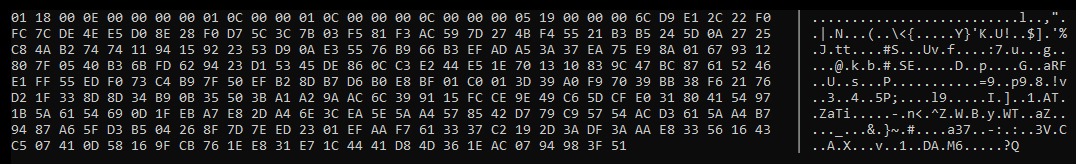

So lets dive right in and see what data the client sends to the server when it first connects, including the encrypted data.

Thats quite the block of seemingly unintelligible bytes.

However if you look careful at the first few bytes you will notice the data has fairly low entropy - lots of repeating zeros for example. Following this block the remainder of the bytes look to be exactly the opposite - very high entropy.

We can take a reasoned guess that the low-entry bytes at the start are a header of some description, describing the block of encrypted bytes that follow. You will see similarly structured data in a lot of protocols that use TCP, as they make it simpler to break up the stream of data into individually processed packets, this is typically known as message framing.

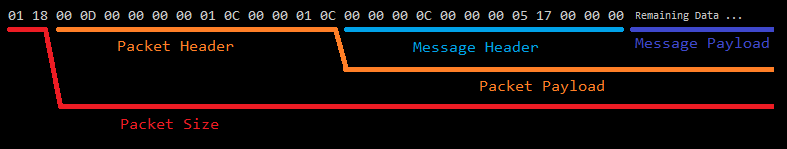

Looking at the header in more detail we can start to break down what it actually contains:

In total we have 26 bytes we need to decipher the format of.

The first 2 bytes are easy to figure out - to deliminate a stream of data into individual packets we need to know the amount of data to recieve before processing it. The first 2 bytes are 01 18 (decimal 280) which is exactly equal to the length of remaining data after it.

struct message_header

{

uint16_t payload_size;

uint8_t unknown[24];

};

We can guess, from the repeated runs of zeros, that the remainder of the header is likely made up of multiple big-endian multi-byte fields which contain small values. If we break the buffer up assuming the non-zero values are in the most-significant bytes, we can get a rough idea of the structure.

struct message_header

{

uint16_t payload_size;

uint16_t unknown_1;

uint8_t unknown_2;

uint8_t unknown_3;

uint32_t unknown_4;

uint32_t unknown_5;

uint32_t unknown_6;

uint32_t unknown_7;

uint8_t unknown_8;

uint8_t unknown_9;

uint8_t unknown_10;

uint8_t unknown_11;

};

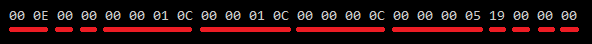

We can use a simple trick to start breaking down these values. By trying to connect multiple times in a row, we can see what changes in the packet each time, this allows us to seperate out any dynamic data from static data.

We can see that the the first value and last value seem to increase each time we try to connect. These are likely sequence-numbers of some description, possibly for matching up request packets and responses.

If we do this enough times to overflow the last value we will also discover that it is stored in little-endian, the opposite of the other fields.

struct packet_header

{

uint16_t payload_size;

uint16_t sequence_number_1;

uint8_t unknown_2;

uint8_t unknown_3;

uint32_t unknown_4;

uint32_t unknown_5;

uint32_t unknown_6;

uint32_t unknown_7;

uint32_t sequence_number_2_little_endian;

};

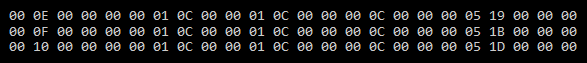

If we look at the values in each of these fields we will see 2 with the repeated value 01 0C (decimal 268), which is the number of bytes that follow the after these specific fields.

What we are looking at here is nested-protocols. We have a packet, who’s payload contains a message, whos payload contains the actual encrypted data. Both the message and the packet have a header, they are adjacent in memory causing us to currently assume they are a single header. If we break this into multiple structures and annotate the lengths we can start to make more sense of this.

struct packet_prefix

{

uint16_t packet_size;

};

struct packet_header

{

uint16_t sequence_number_1;

uint8_t unknown_2;

uint8_t unknown_3;

uint32_t payload_length;

uint32_t payload_length_2;

};

struct message_header

{

uint32_t unknown_6;

uint32_t unknown_7;

uint32_t sequence_number_2_little_endian;

};

Trivia: I have no idea why the protocol duplicates the payload_length field, its a bit of an oddity. Perhaps a left over from previous iterations?

Now that we have disambiguated the message header from the packet header, some of our values become easier to determine.

We can now determine that unknown_2 and unknown_3, which are always 0, are almost certainly compiler-added padding to ensure that payload_length has correct alignment.

We can also determine the 2 sequence numbers are part of different frames of data - one is for packets, one is for messages.

struct packet_prefix

{

uint16_t packet_size;

};

struct packet_header

{

uint16_t sequence;

uint8_t padding[2];

uint32_t payload_length;

uint32_t payload_length_2;

};

struct message_header

{

uint32_t unknown_6;

uint32_t unknown_7;

uint32_t sequence;

};

unknown_6 looks to always be 0C (decimal 12), which is the same size as message_header, and we can assume is likely just a prefix-size in case of variable-length headers.

unknown_7 is a little more tricky, but we can make some educated assumptions that allow us to fill it in. The game needs some way to known what type of message is contained in the payload, so it knows how it should parse it. We can further reinforce this assumption, by tracing through all the packets send during the games connection to the server, and seeing that this value is always sent in the same sequence.

struct packet_prefix

{

uint16_t packet_size;

};

struct packet_header

{

uint16_t sequence;

uint8_t padding[2];

uint32_t payload_length;

uint32_t payload_length_2;

};

enum class message_type

{

initial_message = 5,

};

struct message_header

{

uint32_t header_size;

message_type type;

uint32_t sequence;

};

One thing remains to be deciphered before we known enough to send and recieve a stream of packets, and its a bit of an oddity.

If we look at replies recieved from the server, there are a few things we might notice.

The first and most obvious thing to notice is the header is longer.

Any responses to a clients request messages have 16 additional bytes added to the end of the message_header. The value of these 16 bytes is always static, and never changes. The values are 4 uint32_t’s with the second having a value of 1 and the rest a value of 0.

Along with that its also worth noting that replies always have a message type of 0, and a sequence number that matches the initial message that prompted the reply, which confirms our assumption earlier.

struct packet_prefix

{

uint16_t packet_size;

};

struct packet_header

{

uint16_t sequence;

uint8_t padding[2];

uint32_t payload_length;

uint32_t payload_length_2;

};

enum class message_type

{

reply = 0,

initial_message = 5,

};

struct message_header

{

uint32_t header_size;

message_type type;

uint32_t sequence;

};

struct message_response_header

{

uint32_t unknown_1 = 0;

uint32_t unknown_2 = 1;

uint32_t unknown_3 = 0;

uint32_t unknown_4 = 0;

};

I’ve never been able to determine the point of these values, they don’t do anything, and the game doesn’t appear to use them in any way. I’m guessing they are perhaps left overs from previous iterations of the protocol.

The Message Payload

At this point we have enough information to emulate the sending and receiving of messages from the game server. However we do not yet know how the payload of the message is structured.

The first step is to get it decrypted. With the keypair we made in the previous part of this guide, we can now decrypt it using the private key. Using OpenSSL we just need to make a call to RSA_private_encrypt.

The padding mode depends on which side of the connection we are on, the client encrypts using RSA_PKCS1_OAEP_PADDING, while the server encrypts using RSA_X931_PADDING, this can be confirmed by breakpointing the RSA encryption and decryption functions in a debugger.

As our encryption is asymmetric, you may be asking how the client decrypts messages send by the server if it only has a public key. To do this the game exploits an interesting quirk of RSA cryptography, its possible to encrypt with the private key and decrypt with the public key. This is exactly what happens when the server sends the client message. For anyone contemplating doing this though, don’t, it’s terrible for a number of reasons. You can read some of these reasons here, written by someone far more knowledgeable about cryptography than myself.

So anyway, once we’ve decrypted the first message payload, what exactly do we get?

Note: I’ve censored part of this to hide personal information.

So what is this exactly? Well just looking at the text representation you can see at least one string of characters - the uint64 representation of my steam-id infact. But how exactly do we decipher this, there aren’t any obvious patterns we can abuse like the repeating zeros in the packet headers.

Well this one requires a bit more investigation of the exe in ghidra.

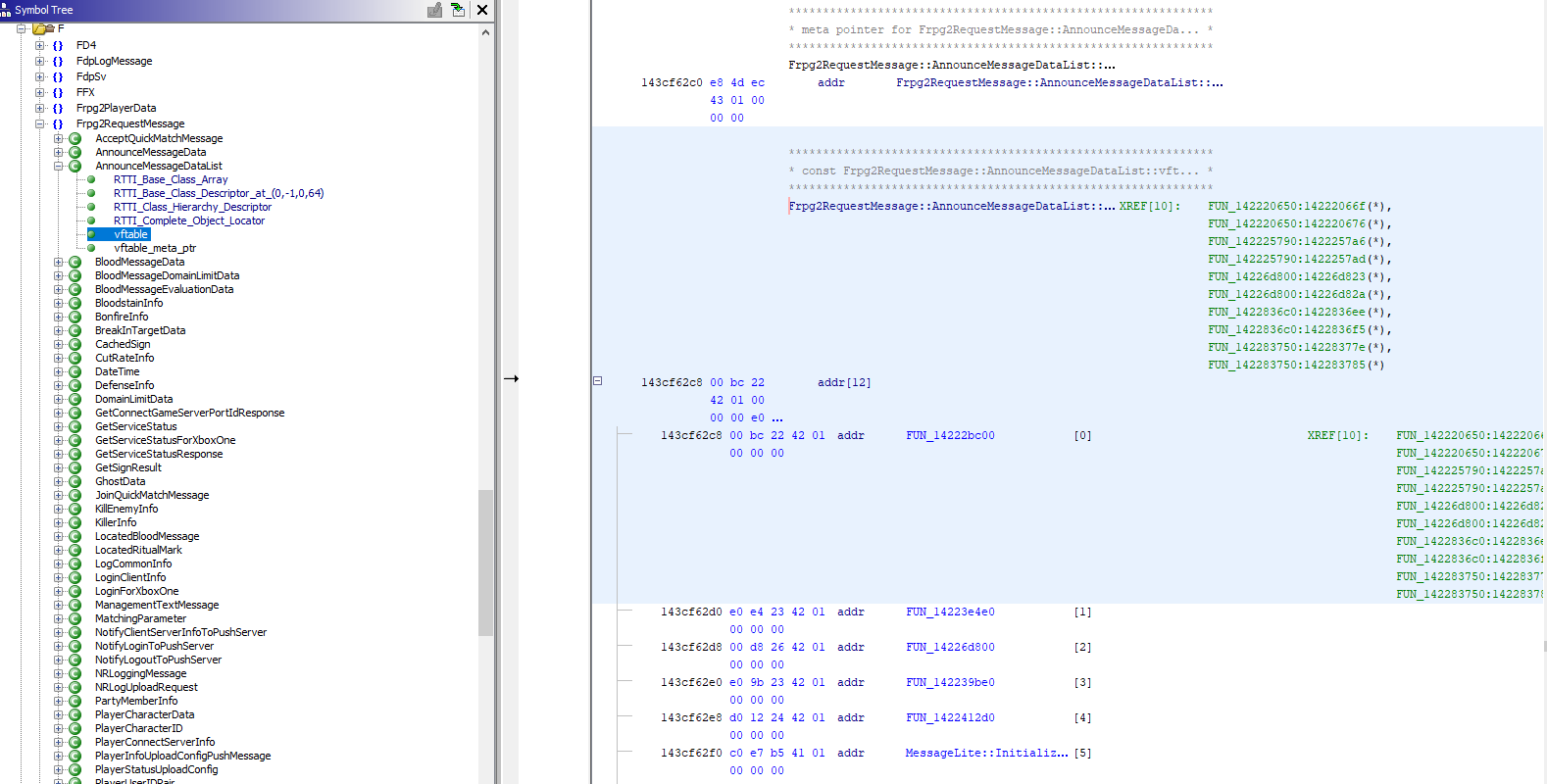

If we look around at the code the Nauru namespace references, you will see a lot of RTTI references to types such as “MessageLite”. A quick google search will show us that these types are part of Protocol Buffers (typically shortened to Protobuf), google’s structured data serialization format. And if we look even further we will a couple of namespaces (Frpg2RequestMessage and Frpg2PlayerData) that contain a whole lot of types with MessageLite related functions in their virtual function table.

Protobuf works by having its own compiler that generates compilable code for a specific language, this code is then capable of serializing protobuf data structures. These data structures are defined in a language-neutral .proto files that look something like this:

message Person {

required string name = 1;

required int32 id = 2;

optional string email = 3;

}

Note: For people unfamiliar with .proto syntax, the equals value is assigning each field an index used for matching up serialized values to the fields, its not setting a field’s value!

The RTTI types we’ve found are for the classes that were generated by the protobuf compiler. One of which exists for each message that is sent across the connection!

Unfortunately the source .proto files are not shipped with the game. So now all we need to do is create our own .proto file that matches the data and we can deserialize and manipulate it easily!

Reverse-Engineering Protobufs

Unfortunately its not that easy :(

The data format on the wire is tightly packed, and has no references to the original field names only their numeric indices. So if we need to reverse-engineer the contents of the original .proto file (which is not packed with the game) so we can have protobuf generate valid serialization code for the data.

This was probably the most time-consuming part of making DS3OS. Especially as the game makes use of the “MessageLite” format of protobufs, which strips out a lot of the useful metadata from the executable and serialized data, that would make them easier to decipher.

There are two useful tools we can use to make this process easier.

If we log each protobuf received we can use the –decode option in Protobuf compiler (protoc). This will show us the field number, value and data type of each field in the provided protobuf. However while useful, this is very problematic when optional fields are defined, or for messages we cannot get captures of easily.

A much more robust way we can do this is to read the parsing code in Ghidra, and reconstruct the fields from there. Index 7 in the vtable of each type is the deserialization function.

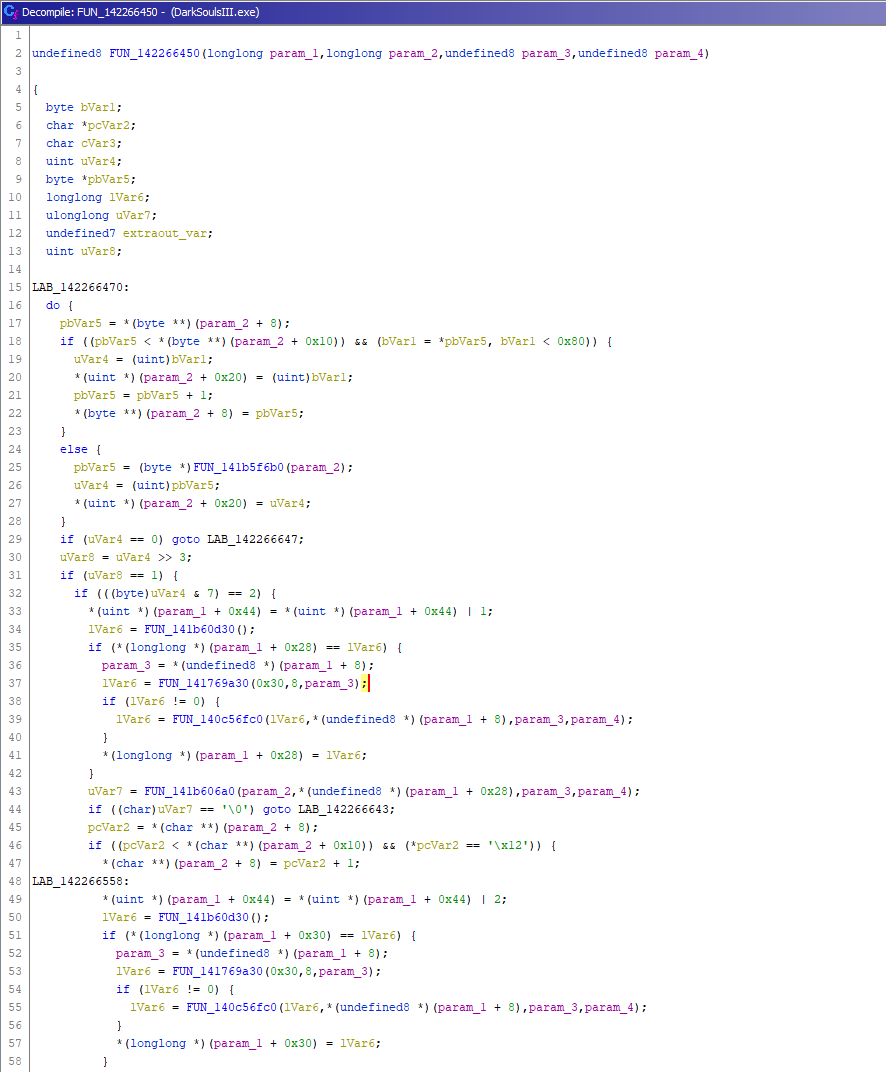

Take for example the following Protobuf deserialization function (this is for the message called RequestQueryLoginServerInfo).

This might seem indecipherable, but if we know one single thing about the protobuf wire format (lots of info about the format here) it becomes much easier to understand.

Prefixed before each field in the protobuf wire format is a uint16_t whose first 3 bits are the format of the field, and the remaining bits are the fields index. This leads to a very common pattern in the disassembled code:

uVar8 = uVar4 >> 3;

if (uVar8 == 1) {

if (((byte)uVar4 & 7) == 2) {

We can see uVar8 is shifting off the first 3 bits of uVar4. So we can assume here its trying to get the field index. We can also see further below that we are bitwise-and’ing uVar4 with 7, which in effect retrieves the field data type. You can rewrite the above code like this:

field_index = field_prefix >> 3;

if (field_index == 1) {

field_data_type = ((byte)field_prefix & 7)

if (field_data_type == 2) {

Because the protobuf code is generated, its consistent and follows the same pattern everywhere, checking for field index and then checking is the correct data type, before parsing the value. We can examine all the classes to build up a .protobuf file that matches the original one that we don’t have access to.

After this point its just a matter of figuring out what each of the fields actually does, which is just a matter of looking at which messages are sent in which situations and applying some deduction.

The Login Flow

So assuming we have reverse engineered all the protobufs, what exactly is the initial packet thats sent on connection.

It turns out the protobuf that the received data matches up to is RequestQueryLoginServerInfo, which has the following protobuf representation:

message RequestQueryLoginServerInfo {

required string steam_id = 1;

optional string unknown_2 = 2;

// app version without the period and -1. eg. app ver 1.13 = 112

required uint64 app_version = 3;

}

The server always responds to this with a RequestQueryLoginServerInfoResponse protobuf message:

message RequestQueryLoginServerInfoResponse {

required int64 port = 1;

required string server_ip = 2;

}

As you might have guessed from the names. The original server the client communicates with acts as an introduction server, taking some basic details and telling them which server they should communicate with next.

In general the retail server will always direct the user to the same server & port, I imagine this might direct users to different servers in pre-release/press/development scenarios.

Coming up

In the next post I’ll be going over what the next server in the chain is responsible for (Oh by the way, its a chain, we get forwarded to other exciting servers after the next one!).