Reverse Engineering Dark Souls 3 Networking (#3 - Key Exchange)

Recap

In the last post I described knowledge how the basic messaging protocol works, and we left off with the server redirecting the client to another server. In this post we will be looking at what function this second server performs.

From this point forward we’re going to be passing a lot of different message types around, so I’m not going to discuss how each of them were reverse-engineered in detail, as it’s the same process of logical deductions and investigation described in the previous post.

Firm Handshakes All Around

So lets dive in and have a look at this new server. Fortunately this server uses the same tcp protocol as the previous one, so we can already use our previous knowledge to decipher it.

As soon as the game connects it sends a message (with a type value of 6), containing a protobuf called RequestHandshake.

message RequestHandshake {

required bytes unknown_1 = 1;

}

Once the client sends this to the server, something unusual happens. The server replies with a response message, with a 27 byte payload, which is both un-encrypted and isn’t parsable as a protobuf. As soon as the game receives this all messages that follow are not longer decryptable!

So what exactly is going on here? If we have a look at the unknown field in the RequestHandshake message as well as the response, we can get get an idea.

Looking at the header in more detail we can start to break down what it actually contains:

If we run the process multiple times we can also see that the values are never consistent, and appear totally random.

Got an inkling of whats going on here yet?

It’s a key-exchange! By the time we get into the game we will be sending a lot of messages often, and RSA just isn’t suitable for doing. It’s encryption and decryption costs are infeasible for realtime usage. So the server and game exchange key material from which to derive a symmetric key for a more lightweight encryption algorithm.

Normally what happens in this situation is both game and server send each other a few bytes of random data and combine them together in a deterministic way to come to a shared conclusion on the key they should use for future communications.

However Dark Souls 3 appears to be broken in this regard (a phrase you might want to get used to …). The key material the server sends back is entirely unused. The key used for all future communications is the raw 16 bytes that the game initially sends.

So what cipher does the game use for all future communications if not RSA? It uses a very obscure ones, that as far as I’m aware only has a single implementation public on the internet - in the original authors GitHub. The cipher is AES-CWC-128, as hinted to by the CWCObject we found when looking through the RTTI types in the previous post.

Also if you wanted to use the reference implementation, you might be disappointed! FromSoftware for whatever reason decided to flip the endian of some calculations in the middle of the implementation (at line 498 of cwc.c if your curious). Good job to the guys on the ?ServerName? discord who managed to figure out that nightmare.

Authentication Flow

So now that we have swapped encryption to a new cipher, what else does this server actually do?

Well this server can process and respond to the following 3 different types of messages. These messages are always sent in the same order from the game. Additional flows might exist in development scenarios.

Service Status

The next thing the game does is send a message (type 2) containing the following protobuf.

message GetServiceStatus {

required int64 id = 1;

required string steam_id = 2;

optional string unknown_1 = 3;

required int64 app_version = 4;

}

This essentially is asking the server if a given service is available to us with the version and steam-id we are using. The game currently only queries a service with an id of 2, which appears to just refer to the standard online game features.

The response sent to the client is almost identical to the request, with the exception of the steam-id being blank.

message GetServiceStatusResponse {

optional int64 id = 1;

optional string steam_id = 2;

optional int64 unknown_1 = 3;

optional int64 app_version = 4;

}

If the user is using an out of date version of the game, the server will send back an empty response with no fields set. If the game receives a response like this it will show a message telling the user to update their game.

Key Exchange Redux

Surprise! You thought we had already exchanged encryption keys earlier. Well guess what, we’re going to do it again!

This begins with a message (of type 1) with a payload containing 8 bytes, which are not parsable as a protobuf.

The response send is a message containing a payload of 16 bytes. Lets have a look at the request and response:

Looks like the server just tacks on 8 random bytes to the 8 the client send and then sends the 16 byte result back.

And guess what? This works correctly, the derived bytes are what is actually used as a key this time.

But what is this key even for? We shall find out soon!

Ticket Authentication

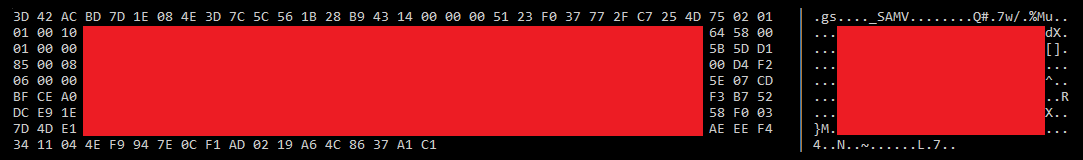

Now we’re getting to the meat of things. The next message that’s sent (of type 3) contains a variable length, non-protobuf payload. Lets have a look at it shall we?

Partially redacted to avoid any potential spoofing of my steam account.

Partially redacted to avoid any potential spoofing of my steam account.

Looks like a lot of random data? Not quite.

If we look at the first 16 bytes we can see these are the key we generated in the previous step, oddly this is the actual key that ends up getting used in future - I’m not sure what the point of the key exchange was previously if the client can just generate its own key and send the key to the server here, a mystery.

The rest of the bytes are interesting though. They differ each run, and can differ in length -drastically- between different players. We can use a bit of logical deduction here to guess what this is - the game needs some way to verify that the user actually owns the game, and the game uses steam. Could this be a steam ticket? Its roughly the right size and shares the same characteristics?

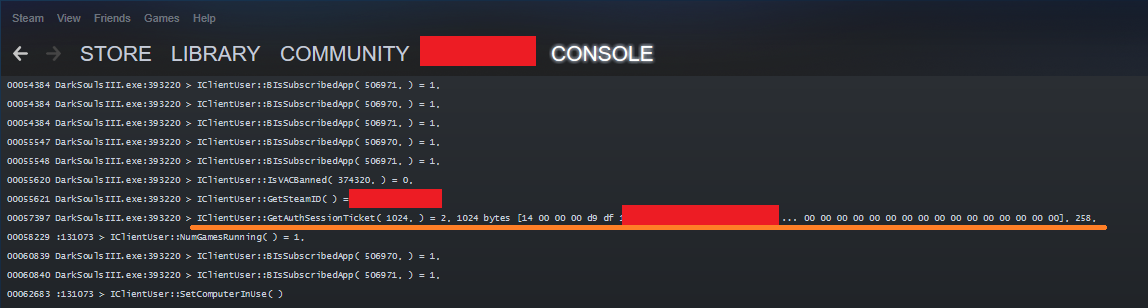

Well we can easily verify this. Steam has a developer mode, one function of which is to write out all API calls and responses that a game performs. You can find lots of documentation about it Here.

Yup, that looks like it matches - the client requests an encrypted ticket just before it communicates with the server, and it looks to be the same length!

At this point, the server authenticates the ticket with the steamworks backend. If the ticket fails to validate the player is abruptly disconnected. If the ticket is validated the server sends a response with an non-protobuf 184 byte payload.

Game Server Info

And oh boy is this payload interesting. Its structured roughly like this:

struct Frpg2GameServerInfo

{

uint64_t auth_token;

char game_server_ip[16];

uint8_t unknown_horror[112];

uint16_t game_port;

uint8_t padding[2];

uint32_t unknown_1 = 0x00008000;

uint32_t unknown_2 = 0x00008000;

uint32_t unknown_3 = 0x0000A000;

uint32_t unknown_4 = 0x0000A000;

uint32_t unknown_5 = 0x00000080;

uint32_t unknown_6 = 0x00008000;

uint32_t unknown_7 = 0x0000A000;

uint32_t unknown_8 = 0x000493E0;

uint32_t unknown_9 = 0x000061A8;

uint32_t unknown_10 = 0x0000000C;

uint32_t unknown_11 = 0;

};

Its main purpose is to provide the client with the ip address and port of the next server it needs to connect to. This server is the final and most important server - the game server which handles all our requests for in-game features, and the topic of the next blog entry.

In the retail environment there are actually two different servers you can be directed to here. If the server has flagged you in the past for cheating, which it does en-mass every week, you will be redirected to a “banned server”. Otherwise you will be redirected to the normal game server. It’s impossible to play with people on other servers, banned players will only be able to play with other banned players, and the same for unbanned players. Banned players are essentially quarantined while still allow them to play online.

This “banned server” is also where anyone playing mods online will end up, which is a massive shame. It means some of the massive overhaul mods like Cinders can only play online on servers filled with people cheating. This was one of the main reasons for writing DS3OS, it gives somewhere safe for people with modded games to play.

Before we start looking at the next server, there are some entries in this structure that are quite interesting.

auth_token its a randomly generated number we will be using on the game server to tell it we have been authenticated by this server and to let us connect. We will go more into detail about how this fits into things in the future.

unknown_1 through unknown_11 haven’t been investigated much yet. They must be set to the values shown above though or the game will crash. I speculate from the behavior I’ve seen that that these are potentially configuration values for memory allocation, they have very suspicious power-of-two-ey numbers which definitely makes me believe they were defined by a programmer.

unknown_horror however is where the real fun is. It’s uninitialized data, which appears to be leaking parts of the stack on the game server. Uh-oh. Given the security problems the Dark Soul’s games have recently been notorious for (Info here for those out of the loop), it really does feel like FromSoftware should probably hire some pen-testers and audit their network code.

But anyhow, we have our destination, so onwards to the game server!

Coming Up

This was a fairly short post as the “authentication” server doesn’t do a whole lot, but is an important piece of the network architecture. In the next blog post we are going to start looking into the game-server, and it’s going to get -chonky- as there are a lot of things to go over for it. But we’re almost to the point where we can start looking at game-visible mechanics!